Journal: Hospital Practice

Publisher: Taylor and Francis

Maxwell Obubu, Nkata Chuku, Alozie Ananaba, Firdausi Umar Sadiq, Emmanuel Sambo, Oluwatosin Kolade, Tolulope Oyekanmi, Kehinde Olaosebikan & Oluwafemi Serrano

Received 18 Nov 2022, Accepted 17 Jan 2023, Accepted author version posted online: 02 Feb 2023, Published online: 06 Feb 2023

Download citation https://doi.org/10.1080/21548331.2023.2170651

ABSTRACT

Background

Nigeria is considering making Universal Health Coverage (UHC) a common policy goal to ensure that citizens have access to high-quality healthcare services without crippling debt. Globally, there is an acute shortage of human resources for Health (HRH), and the most significant burden is borne by low-income countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. This shortage has considerably constrained the achievement of health-related development goals and impeded accelerated progress toward universal health coverage. We examine the existing human resource capacity and the distribution of health facilities in Lagos state in this study, discussing the implications of our findings.

Methods

The study is descriptive using secondary data analysis. We leverage census-based primary data collected by NOIPoll on health facility assessments in Lagos state. The collected data was analyzed using counts, ratios, rates, and percentages.

Results

We observe a ratio of 5,014 people to 1 general medical doctor, 2,942 people to 1 specialist, 2,165 people to 1 nurse, and 5,117 people to 1 midwife, which are far higher than the WHO recommendation. We also observe that the ratio of nurses to general medical practitioners is 2.2:1 in urban areas and 2.7:1 in rural. In contrast, the ratio of nurses to specialist medical doctors is 1.3:1 in the urban area and 1.5:1 in the rural areas of Lagos state. The overall nurse per general medical practitioner ratio is 2.3:1 and 1.4:1 for specialist medical doctors. 77.2% of the health facilities surveyed were in the urban areas, with private-for-profit facilities accounting for 82.9%, government facilities accounting for 15.4%, and NGOs/faith clinics accounting for 1.7%. Primary healthcare facilities account for 75.3% of the facilities surveyed, secondary and tertiary facilities account for 24.6% and 0.08%, respectively. Alimosho LGA has the most health facilities (77.38% PHCs, and 22.62% SHCs) and staff strength specifically for general medical practitioners, specialists, nurses, and midwives (16.9%, 19.9%, 16.7%, 17.1%, respectively). Eti-Osa LGA has the best density ratio for generalist doctors, specialist doctors, and nurses per 10,000 (4.42, 12.96, and 11.34 respectively), while Ikeja has the best midwife population density ratio 5.46 per 10,000 population.

Conclusion

The distribution of health personnel and facilities in Lagos State is not equitable, with evident variation between rural and urban areas. This inequitable distribution could affect the physical distance of health facilities to residents, leading to decreased utilization, ultimately poor health outcomes, and impaired access. Much like child mortality, maternal mortality also exhibits a correlation with healthcare worker density. As the physician density increases linearly, the maternal mortality rate decreases exponentially. However, due to the low number of healthcare workers in Lagos state, doctors, nurses, and midwives are frequently unavailable during childbirth, resulting in increasing infant, neonatal, and maternal death. As such, the government should adopt the UHC strategy in its distribution of facilities and personnel in the state for adequate coverage and optimal performance of the facilities. Also, additional investments are needed in some parts of the state to improve access to tertiary health facilities and leverage private sector capacity.

Introduction

Health systems can only function with health workers; improving health service coverage and outcomes depend on a fit-for-purpose and fit-to-practice health workforce [1,2]. We expect significant growth in the need for health workers globally in the coming decades due to various factors, including population growth, aging, changing epidemiology, and new technologies [3,4]. As stated in the declaration of the international conference on primary health care held in Alma Ata, Russia, in 1978, the primary objective of primary health care is better health for all. This includes ensuring that healthcare is accessible, equitable, and affordable [4]. According to a 2008 WHO report, significant progress in health has largely been unevenly distributed globally, with convergence toward better health in many regions of the world. Many nations are falling behind with growing health disparities within countries [4]. Equity in health care is based on the idea that everyone should have access to high-quality medical care [5]. Most healthcare systems are based on the idea that human resources should be used fairly and equally for the benefit of the entire population. Access to healthcare has a direct impact on disease burden, especially in developing countries, and is a crucial determinant of the overall effectiveness of a healthcare delivery system. Health systems in various populations have benefited from increased access to healthcare [6]. Measuring healthcare access, therefore, aids in developing a more comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of the health system [7,8]. Achieving the goal of universal health care is unfortunately difficult because not everyone can access health care services equally [9]. According to Atser and Akpan [10], variation in the distribution of facilities is essential, particularly in rural areas where there are issues with a lack of facilities and the mobility of health personnel. A study conducted in the Ondo state revealed that the distribution of healthcare facilities was inequitable, which constrained the advancement of health at the community level [11]. In a study on health deprivation in rural Borno, Nigeria, Adedayo and Yusuf [12] concluded that health deprivation lowers the quality of life in rural communities. Overcrowding, a resulting lack of proper attention to patients, and poor access in some specific areas with vulnerable conditions of the low number of health facilities, especially among rural residents, are the effects of the maldistribution of health facilities [13,14].

Health policymakers must prioritize ensuring that all people have access to primary healthcare equally. All citizens in a nation’s most remote and impoverished areas should hav access to healthcare professionals. The provision of healthcare is both a necessity for society and a fundamental human right. A lack of healthcare staff, basic health facilities, and services in any community links to lower productivity, shorter life expectancy, and higher death rates []. Nigeria has faced several shortcomings in managing its health system over decades resulting in repeated reforms [16–19]. Unfortunately, these reforms hav e not significantly impacted the health status of the 184 million residents [20–22]. National health systems in Niger ia are known to perform below expectations due to recurring issues both within and outside the health sector, limiting affordable healthcare services to the people [23]. The health system’s functional capa cities in these settings have gradually deteriorated due to failure to recognize and utilize the efforts of all organizations, institutions, structures, and resources primarily focused on promoting health [24]. Several studies link the presence of health workers to a favorable health outcome [25]. As a result, its availability and composition are recognized as crucial indicators of the health systems strengthening. The World health report 2006 suggests a minimum worker density threshold of 2.3 workers (doctors, nurses, and midwives) per 1000 population necessary to achieve the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for health [25]. However, there is no broad agreement on the optimal number of health workers required for a given population [25]. In the distribution of health workers, inequalities could be in the form of chronic or acute personnel shortages in some locations or professional misdistribution [26]. This problem crosses around the world, but especially in Low-to-middle-income countries. As a result, there is a need for Equity in the distribution of healthcare facilities. Both accessibility and use are critical features of equitable health resource distribution based on population needs rather than equal distribution in terms of number [27]. The distance between health facilities and residents in Lagos State is a significant factor influencing health service utilization and health outcomes, and increasing distance lead to lower utilization. Therefore, access to health facilities plays a critical role in improving the health status of people [28]. According to Eke (2015; Sanni, 2010) [29], the Nigerian healthcare sector is severely underdeveloped and fails to satisfy local demands because most healthcare facilities concentrate in major cities, with residents in urban areas having four times the amount of access to healthcare as those in rural areas. The health infrastructure in Nigeria is inadequate to meet the growing population’s needs [< href="https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21548331.2023.2170651">29]. Nigeria was ranked 140th out of 195 countries on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index report, based on quantifying personal access to healthcare and the quality of healthcare offered in 195 countries from 1990 to 2015 [30]. Because of the poor healthcare situation in the country, roughly 715 doctors left in 2015, leaving Nigeria with a doctor-to-patient ratio of 1:4250, compared to the recommended ratio of 1:600 by the World Health Organization [30,31]. Inequalities in the geographical distribution of healthcare facilities are a crucial constraint on access to healthcare services. The distance between the location of the health facility, its high demand, and the shortage of personnel contributes to the difficulty of using the healthcare services [32,33]. Uwala (2020) and Welcome (2011) [34,35] also stated that health facilities (health centers, workers, and medical equipment) are insufficient, particularly in rural regions. As a result, this study aims to assess the existing human resources capacity in health facilities in Lagos State, Nigeria. The research questions guiding the study are:

- How are Lagos State healthcare facilities distributed?

- Are healthcare personnel in Lagos State adequate and evenly distributed across the local governments in the state?

- What is the ratio of facility and personnel (doctors, nurses, and midwives) to the population in Lagos State?

Study area

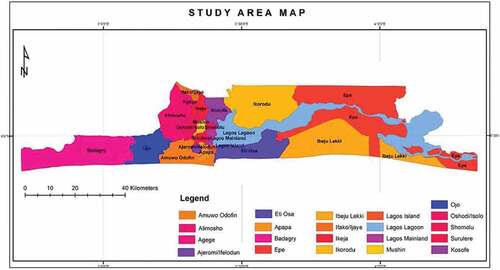

Lagos is one of the 36 states in Nigeria, with the year 2020 estimated population of 14,368,000 [36]. Lagos is Nigeria’s most densely populated state, accounting for approximately 7% of the national population [37–40]. It has five administrative divis ions: Ikeja, Badagry, Ikorodu, Lagos Island, and Epe, subdivided into 20 Local Government Areas (LGAs) (Figure 1). Lagos State has 358,862 hectares or 3,577 sq. km, accounting for approximately 0.4% of the total land area in Nigeria. The state covers 356,861 hectares, with wetlands covering 75,755 hectares [41]. The state is in the southwestern part of Nigeria [41–44]. According to the United Nations, if Lagos state continues at its current growth rate, it will soon double its current population size, making it the third most populous large city, trailing only Tokyo and Delhi (U.N. 2016) [42]. Lagos State has a total hospital/clinic population of 2,333: 458 public and 1875 private, out of which 1574 are primary health facilities, 756 are secondary, and three are tertiary. Of this number, public/primary is 412, private/primary is 1162, public/secondary are 44, private/secondary is 712, public/tertiary is two, and private/tertiary is one [45]. Over the last decade, the state has made significant progress in the economy, infrastructure, and healthcare systems. According to the Health Facility Monitoring and Accreditation Agency (HEFAMAA), the Lagos State Government has significantly improved health systems by acquiring vaccinations and family planning programs. According to HEFAMAA, Lagos has over 10,000 skilled healthcare workers across 20 local governments. It has over 2,500 accredited healthcare facilities (private and public-owned) providing healthcare services in the state, including Primary Health Centers, Maternal/Child Health Clinics, Specialist Clinics, and Diagnostic Centers. While these facilities provide access to health education, the constant rate of avoidable deaths in Lagos, particularly maternal and child mortality, is deeply concerning.

Figure 1. Map of Lagos showing the Local Government Areas. Source: Ministry of Physical Planning.

Data and sampling methods

The study leveraged Universal Health Coverage data collected on health facilities assessment in Lagos state [46]. NOIPoll carried out the health facility assessment with technical assistance from HSCL. NOIPoll adopted a quantitative research methodology for the health facility assessment, while HSCL developed a list of health facilities using information from the State Ministry of Health. The list served as a sample frame for health facilities in Lagos state. The sample frame consisted of 2,398 health facilities, and a census approach was adopted. NOIPoll engaged vital stakeholders to refine the technical assistance plan for the health facility assessment. These stakeholders include the State Ministry of Health (SMOH), the Lagos State Health Insurance Agency (LASHMA), the Health Facility Monitoring and Accreditation Agency (HEFAMAA), and relevant professional bodies. NOIPoll interviewed target respondents through the telephone using Questionnaire Processing Software for Market Research (QPSMR). The final health facility assessment dataset contains information on Facility Ownership, Facility level of care, Accrediting body, Human Resources, Basic Medical & Infection Prevention Equipment, Infrastructure, Available Services, Health Insurance Coverage, Medicines & Commodities, Financial Management Systems, Clinical Governance, and Covid-19 Response.

Statistical method

The method of analysis employed in the study is descriptive statistics. We use multiple and straightforward bar charts, alongside percentages and ratios, to assess the distribution of facilities and personnel distributions across the state. Also, we computed the estimated population of Local Government Areas in Lagos State for 2020 used in the study using a constant national growth rate of 3.3% and a geometric growth projection method as adopted by CityPopulation (2021) [47]. Because NOIPoll successfully interviewed 1256 facilities, accounting for 53.8% of all health facilities in Lagos State, we compute the facility and health personnel to population ratio using 53.8% of the population in the state.

Results

Distribution of healthcare facilities in Lagos State

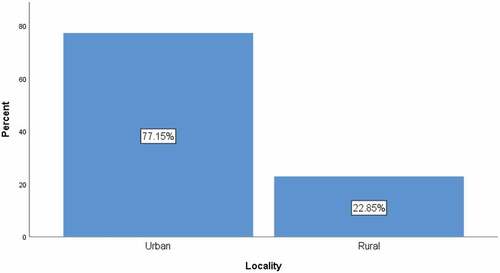

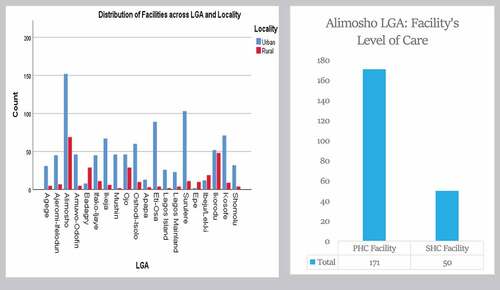

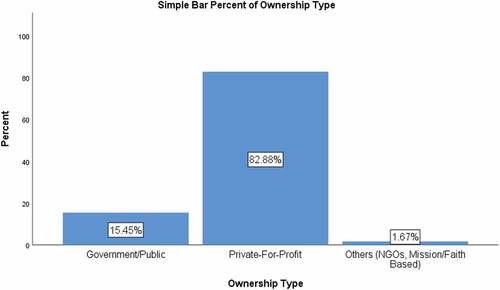

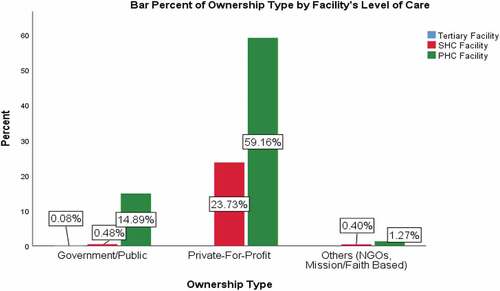

The results of the analyses are presented based on the distribution of healthcare facilities and personnel across Lagos State. Most facilities surveyed (77.15%) are in the state’s ur ban areas, while 22.85% are in the state’s rural areas (See Figure 2). The facilities are concentrated more in Alimosho Local Government Area than any other LGA (See Figure 3). Most of the facilities surveyed (75.32%) are primary health care (PHC), 24.60% are secondary health care (SHC), and 0.08% are tertiary facilities. 55.97% of the facilities are PHC in the urban area, 19.35% are PHC located in the rural area, 21.10% are SHC in the urban area, and 3.50% are SHC located in the rural areas of the State (See FIgure 4). The results also show that most of the facilities surveyed (82.88%) are private-for-profit, with 59.16% being PHCs and 23.73% being SHCs. 15.45% are government-owned facilities, with 14.89% being PHCs, 0.48% are SHCs, and 0.08% are tertiary facilities. 1.67% are NGOs/mission-owned facilities, with 1.27% PHCs and 0.40% SHCs (See Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 2. Percent Distribution of Facilities in Urban and Rural Areas.

Figure 3. The Distribution of Facilities across the Local government area (LGA) and locality.

Figure 4. Distribution of Facility Level of Care in Urban and Rural Areas of the States.

Figure 5. Percent Distribution of Facilities based on Ownership Type.

Figure 6. Percent Distribution of Facility Ownership Type by Level of Care.

Distribution of healthcare personnel in Lagos State

Alimosho LGA has the highest population of general medical doctors (16.9%) with a ratio of 2.33 general medical doctors per 10,000 population. Alimosho also has the highest population of specialist medical doctors (18.9%), nurses (16.7%), and midwives (17.1%) with respective rates per 10,000 population of 4.45, 5.32, and 2.31 (See Table 1 and Table 3). The local government with the second largest population of general medical doctors is Surulere (10.4%), with a ratio of 3.75 per 10,000 population. In comparison, Eti-Osa LGA has the second largest number of specialist medical doctors (11.9%) with a ratio of 12.96 per 10,000 population, followed by Surulere (9.9%) with a ratio of 6.1 per 10,000 population. However, Ifako-Ijaye LGA has a ratio of 6.24 specialist medical doctors per 10,000 population, making it the local government with the second-highest specialist-population ratio. We record the highest percentage of Nurses in the State in Alimosho LGA (16.67%), with a ratio of 5.32 per 10,000 population. Next is Surulere LGA, with 9.43% of nurses representing 7.9 nurses per 10,000 population. The ratio of nurses per 10,000 population in Eti-Osa is 11.43, the highest in the State. We recorded a minor proportion of general medical doctors (0.5%) in Epe LGA, and the local government also has a minuscule percentage of specialist medical doctors (0.1%), nurses (0.5%), and midwives (0.6%) in Lagos State. The results further show that 82.8% of general medical doctors, 81.6% of specialists, 79.9% of nurses, and 79.2% of midwives are in urban areas. 85.1% of GMD, 97% of specialists, 84.5% of nurses, and 77.6% of midwives are in private hospitals. 88.3% of GMD, 73.5% of specialists, 86.5% of nurses, and 91.6% of midwives are in primary healthcare facilities (See Table 2).

Table 1. Percent Distribution of Personnel by LGA.

Table 2. The Percent Distribution of Personnel by Facility Ownership and Level of Care.

The ratio of healthcare facility and personnel to the population in Lagos State

Table 4 shows the ratio of private to public health facilities in each LGA. The highest ratio of (15.3:1) private to the public facility is recorded in Surulere LGA, followed by Kosofe (12.3:1), Epe local government has more public health facilities than the private (1:5), and the ratio in Ibeju/Lekki is (1:1). The local government with the least general medical doctors per 10,000 population is Epe (0.52), specialists (0.19), nurses (1), and midwives (0.58). We present the ratio of medical personnel to the facility in Table 5. The study result shows that Ifako-Ijaye and Ajeromi-Ifelodun LGAs have a ratio of about two general medical doctors to one facility (2:1). In contrast, other local government areas have in the state have at most one general medical doctor per facility. The highest specialist-facility ratio of (4.1:1) is in Ifako-Ijaye LGA, followed by Eti-Osa (3.8:1) and the minor ratio of (0.3:1) in Epe local government. For nurses, Ikeja has the highest ratio of 4:1, followed by Ifako-Ijaye (3.8:1), and the least is Epe (1.3:1). Apapa and Ikeja have the midwives-facility ratios of (2.1:1) and (2:1) while Mushin, Lagos Island, Epe, and Shomolu, being the least, have a ratio of 0.8:1. The nurses per general medical doctor ratio are highest in Badagry and Ibeju-Lekki (3.9:1), while the least is (1.7:1) in Ajeromi-Ifelodun and Island. We recorded the highest ratio of nurses to specialists of (5.5:1) in Ibeju-Lekki, followed by Epe (5.3:1), and the least is Lagos Island (0.8:1) (See Table 6) [Citation48]. The ratio of nurses to specialist medical doctors is 14.5:1 in public health facilities, 1.2:1 in the private-for-profit, and 2:1 in NGO/faith-based health facilities.

Table 3. The Distribution of Medical Personnel per 10,000 Population.

Table 4. The Distribution of Public and Private Facilities per 10,000 population.

Table 5. The Ratio of Medical personnel to Facility across the State.

Table 6. The Ratio of Nurses to Doctors across the State.

Figure 7 shows the correlation between population, facilities, and health personnel. The correlation between population and the number of facilities is positive and strong (0.81), meaning that the higher the population, the high the number of facilities. All the correlation coefficients are positive, suggesting a positive relationship between each pair of variables.

Figure 7. Heatmap showing the correlation between Population density, facilities, and medical personnel.

Discussion of findings

Equity in healthcare

Healthcare equity aims to ensure that everyone can access affordable, culturally competent health care regardless of several factors, including geographical location. Findings revealed that most of the healthcare facilities in Lagos State are in the urban region. While the high number of facilities can be linked to the population in urban areas, the distribution of personnel does not rely on the spread of the population, as the study reveals that some local government areas with fewer populations have better medical personnel-to-population ratios than those with a larger population. This shows that healthcare facilities and personnel are not evenly distributed in Lagos State, as Sanni (2010) [49] supported.

The health worker population ratio is better in the urban area of Lagos than in the rural area, where health services are needed more because of their poorer economic and environmental conditions and high population density. As obtained in Lagos state, a poor health worker-to-population ratio implies increased patient waiting time and excessive workload for the providers, affecting quality efficiency with poor health outcomes. Inadequate human resources in rural health facilities could be a significant impediment in mobilizing a response to health challenges resulting in unsafe, ineffective, inefficient, untimely, and inequitable healthcare. Generally, people living in the state’s rural area have worse health than their urban-dwelling counterparts (Wonca, 2003) [50]. Therefore, controlling the inadequacy of workforce distribution in rural and urban Lagos states would have a salutary effect on healthcare delivery, thereby improving the overall well-being of the residents.

SDG 3.C – Recruitment of the health workforce in developing countries

The available facilities are grossly understaffed and cannot cater to the health needs of the people (Alenoghena, Isah and Isara, (2016) [48]. The ratio of 5,014 persons to 1 general medical doctor, 2,942 persons to 1 specialist, 2,165 persons to 1 nurse, and 5,117 persons to 1 midwife in Lagos state indicates that not much importance is attached to the health of the populace. These figures are far higher than the recommended number of doctors per population of 1:600 (Muanya and Onyenucheya, 2021) [31].

The findings further show that the ratio of nurses to general medical doctors is 2.2:1 in urban areas and 2.7:1 in rural areas. The ratio of nurses to specialist medical doctors is 1.3:1 in the urban and 1.5:1 in the state’s rural areas. The overall nurse per general medical doctor ratio was 2.3:1 and 1.4:1 for the specialist medical doctor, which means that Lagos state needs more nurses in urban and rural areas, as there is a deficit of medical personnel, thereby putting much burden on the available ones. Our findings are consistent with Welcome (2011) [35], who pointed out that the healthcare delivery system in Nigeria is inadequate for the populace. In the last ten years, there have been calls to address these general issues, especially on providing better facilities for disease diagnosis and treatment, improved health workforce welfare and remuneration, and expanded NHIS coverage in the country [51].

SDG 3.8 – Access to quality essential healthcare services

According to Nullis-Kapp (2005) [52], the shortage of health professionals could undermine global efforts to reduce poverty and disease and derail development goals. In her journey to universal health coverage, Lagos state adopts the State health insurance scheme (LASHMA) as an official policy target to ensure access to quality healthcare services for her population without financial hardship. A strategy for achieving UHC requires an analysis of the available infrastructure to deliver the services. However, inadequate human resources and poor health facilities distribution could limit service delivery access, thereby promoting poor health outcomes. The LSHS aims to improve access to quality care by reducing the financial burden of obtaining care for Lagos residents. Public and private healthcare providers are critical to this ambitious insurance rollout. Understanding the distribution of health facilities and human resources for health would aid in engaging providers, the factors influencing their participation in insurance, and expectations from the LSHS. Financial (ability to pay), social (knowledge of and empowerment to access care), and physical access to health services are all examples of access. The Lagos State government must restrengthen the Primary Health Care (PHC) system to ensure that all Lagosians have access to high-quality, effective healthcare services to attain Universal Healthcare Coverage in Lagos. The inequitable distribution of health facilities in Lagos State could affect the physical distance of health facilities to residents, leading to decreased utilization, poor health outcomes, and impaired access [53,54].

SDG 3.1 and 3.2 – Reduce the global maternal, neonatal, and child mortality

Nearly every aspect of the state’s public health is negatively impacted by the lack of sufficient huma resources for healthcare. This shortage has a detrimental effect on both maternal health and HIV/AIDS treatment, in addition to raising mortality rates overall. The Lagos state government is concerned about Nigeria’s maternal mortality rate, which is one of the highest in the world at 512 deaths per 100,000 births [53,54]. In 2015, the United Nations Children’ Fund (UNICEF) projected that the likelihood of a child born in Lagos State dying before age five was 8.1% [55]. The severe shortage of healthcare professionals in Lagos State is strongly correlated with the region’s extremely high mortality rates. An exponential decline in the mortality rate of children under five is correlated with a linear increase in the density of healthcare workers. In its 2006 World Health Report, WHO finds a comparable correlation [56]. One explanation for the association between physician density and child mortality rates in Lagos State is that fewer healthcare professionals mean fewer people can access basic medical services like immunizations and antibiotics. Children who are ill may not have access to treatments and may consequently pass away from conditions that could have been avoided. This interpretation supports the notion that most child deaths worldwide and a sizable portion of adult deaths are avoidable and result from inadequate medical care [57]. Like child mortality, maternal mortality correlates with the number of healthcare workers [58,59]. The maternal mortality rate declines exponentially as physician density increases linearly [60]. Similarly, research has revealed that a rise in births attended by medical professionals is linked to a drop in maternal mortality rates [61]. However, the lack of medical personnel in Lagos State causes a high rate of midwives, nurses, and infant deaths because they are frequently absent during childbirth [62].

Conclusion

Strategically locating and adequately staffing medical facilities is one of the indicators of a country’ health and wealth and the level of care it provides to its citizens and visitors. The study focuses on assessing the distribution of healthcare facilities across Lagos State’s local government areas and localities (urban and rural areas) and the distribution of healthcare personnel and their ratios per 10,000 population. According to the findings, the distribution of both health personnel and facilities in Lagos State is not uniform. Some facilities have more personnel, albeit insufficient than others, and some local government areas have more facilities than others. The ratio of one medical doctor to 5,014 residents, one specialist to 2,942 residents, and one nurse per 2,165 residents indicate that the state does not have sufficient experts in the already insufficient facilities to take care of the health needs of the populace. Therefore, this means that many people do not have access to proper and timely healthcare, which is a cause for concern, especially in this era of a mass exodus of medical personnel to developed countries worldwide.

Recommendations

The crisis in the health facility distribution and human resources for healthcare in Lagos state, Nigeria is a highly multifaceted issue; it is as much of a medical problem as it is social and political. The government and relevant stakeholders can only address the crisis via various short and long-term strategies.

- Findings show a ratio of 5.5 private to 1 public health facility in Lagos state, with some local governments having a ratio of 15:1. The state and local governments need to build more health facilities to cater to the health needs of the exponentially growing population of the state.

- The ratio of 1 general medical doctor to 5,014 people is more than eight times the recommended ratio of 1:600 by the World Health Organization [31]. The government needs to act fast by employing more qualified medical doctors to reduce this acute shortage of doctors in the state and help improve the state’s health system to meet the SDG three of good Health and well-being for all by 2030.

- Only 22.9% of the health facilities assessed are in rural areas. The local government should pay attention to the people’s health in rural areas by making primary healthcare facilities available at accessible locations.

- The government should adopt the universal health coverage (UHC) strategy in its distribution of facilities and personnel in the state for adequate coverage and optimal performance of the facilities.

- The government must reduce the exodus of healthcare professionals from this region to address Lagos State human resources for health crisis effectively. Implementing retention policies is one of the best ways to accomplish this. The WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, which serves as a policy framework for the ethical hiring of healthcare professionals, illustrates this [61]. Its main objective is to address the global shortage of healthcare professionals. This policy’s actual impact on the healthcare crisis in Lagos State and Nigeria is debatable because compliance with it is voluntary. Governments must ensure adherence to the pertinent policies to reduce the emigration of healthcare professionals. In doing this, the government must also enhance the working conditions for healthcare professionals by providing incentive programs for particular medical specialties or additional funding for private or rural clinics. A similar program has already been rolled out in Mali, which has significantly improved healthcare professionals’ retention [61].

- Lagos State must substantially increase its health workforce and limit the loss of its current healthcare professionals. Targeting education is one of the best approaches to convince individuals to pursue careers in the healthcare profession. Governments can provide additional incentives to students who enroll in health-related post-secondary programs, and this could be in the form of bursaries, grants, and scholarships. Additionally, medical school entrance requirements may be lowered to allow more students to pursue this career path. Governments can raise the retirement age for physicians and other medical professionals outside the education sector.

- The Lagos state government can also accelerate the implementation of task shifting, Task sharing strategies in all primary healthcare centers within the state. Task-shifting strategies are short-term strategies that require minimal resources. Transfer responsibilities from a highly trained healthcare worker, such as a physician or surgeon, to a less trained healthcare worker, such as a nurse or community healthcare worker, is known as task shifting [63,64]. This approach enables employees with less training to complete tasks that would otherwise go unfinished due to a shortage of employees with more training. This strategy is particularly effective in areas where nurses outnumber doctors, such as the case with Lagos State [65]. Other research on task-shifting strategies in Sub-Saharan Africa has found that this strategy improves health outcomes in general [66,67]. While task-shifting strategies have shown promise, they are not without flaws. Most importantly, when a lower-skilled healthcare worker performs a more demanding task, the quality of care may decrease. As a result, task-shifting strategies should not be considered a panacea but instead in conjunction with other techniques to address the Lagos state healthcare crisis.

Declaration of funding

This research is part of the work supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) through the Nigerian State-Led Strategic Purchasing for Family Planning grant [grant number: INV-007359] assigned to HSCL.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

- Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, et al. A universal truth: no health without a workforce. Forum report, third global forum on human resources for health, Recife, Brazil. Geneva: Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Progress for children: a report card on adolescents. Number 10, April 2012. United Nations Children’s Fund; 2012. [cited 2022 Jan]. Availabl from: http://www.unicef.org/publications/index_62280.html [Google Scholar]

- Online consultation on the WHO Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030. Geneva: world Health Organization. [cited 2022 Feb]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/online_consult-globstrat_hrh/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Technical notes: Global Health Workforce Statistics database. Geneva: world Health Organization. [cited 2022 Feb]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/statistics/TechnicalNotes.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gauld R, Blank R, Burgers J, et al. (2012) The world health report 2008—primary healthcare: How Wide I the Gap between Its Agenda and Implementation in 12 High-Income Health Systems? Healthcare Policy, 7, 38–58.[Google Scholar]

- Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promot Int. 2000;6(3):217–228. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Macinko J, SHI L, MACINKO J. Contribution of Primary Care to Health Systems and Health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Kibon UA, Ahmed M. Distribution of primary health care facilities in kano metropolis using GIS (Geographic Information System). Environ. Earth Sci. 2013;5(4):167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhafiz A, Abdel-Samea M (2013) GIS for Health Services. 1396-1405. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Perry B, Gesler W. Physical access to primary health care in Andean Bolivia. Soc sci med. 2000;50(9):1177–1188. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Atser J, Akpan P. Spatial distribution and accessibility of health facilities in akwa ibom state, Nigeria. Ethiop j environ stud manag. 2009;2(2):49–57. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Umar J, Bolanle W. Locational distribution of health care facilities in the rural area of Ondo State. J Educ Soc Behav Sci. 2015;11(1):1–8. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Adedayo A, Yusuf RO. Health deprivation in rural settlements of borno state, Nigeria. J. Geogr. Geol. Environ. 2012;4(4):52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ujoh F, Kwaghsende F. Analysis of the spatial distribution of health facilities in Benue state, Nigeria. Public Health Res. 2014;4:210–218. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu UA, Kolo MA, Chutiyami M. Analysis of distribution, capacity, and utilization of public health facilities in Borno, North-Eastern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(39):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Asuzu MC. The necessity for a health systems reform in Nigeria. J Community Med Prim Health Care. 2005;16(1):1–3.&n bsp;[Google Scholar]

- Reid M. Nigeria is still searching for the right formula. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(9):663–665. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Emuakpor A. The evolution of health care systems in Nigeria: which way forward in the twenty-first century. Niger Med J. 2010;51(2):53. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley-Gyado R, Filani O, Morhason-Bello I, et al. Strengthening the primary care delivery system: a catalytic investment towards achieving universal health coverage in Nigeria. Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(4):277–284. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Nigeria: country profiles. WHO. http://www.who.int/gho/countries/nga/country_profiles/en/. Published 2014. Accessed 2014 Jul 10 [Google Scholar]

- National Population Commission, Federal Republic of Nigeria, ICF International, Maryland USA. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja Nigeria & Rockville Maryland USA: National Population Commission; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2014. Geneva Switzerland; 2014. [cited 2022 Jun]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112738/1/9789240692671_eng.pdf?ua=1[Google Scholar]

- Adeloye D, David RA, Olaogun AA, et al. Health workforce and governance: the crisis in Nigeria. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(32):1–9. [PubMed], [Google Scholar]

- Sigh P, Sachs JD. (2013). One million community health workers in sub-Saharan Africa by 2015. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):363–365. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Drager S, Gedik G, Poz M (2006). Health workforce issues and the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria: an analytical review, Human Resources for Health 2006, 4:23. [cited 2022 Jun]. Available from: https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1478-4491-4-23.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ekenna A, Itanyi IU, Nwokoro U, et al. How ready is the system to deliver primary healthcare? Results of a primary health facility assessment in Enugu state, Nigeria, health policy and planning. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35:97–106. [Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Omrani-Khoo H, LotfiF, Safari H, et al. Equity in distribution of health care resources; assessment of need and access, using three practical indicators, Iranian. J Publ Health. 2013;42(11):1299–1308. [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Makinde AO, Sule A, Ayankogbe O, et al. Distribution of health facilities in Nigeria: implications and options for universal health coverage. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018;33(3):1179–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Eke C (2015). Healthcare Resource Guide: Nigeria. [cited 2022 Jun]. Available from: https://2016.export.gov/industry/health/healthcareresourceguide/eg_main_092285.asp[Google Scholar]

- Nigeria’ poor healthcare access ranking (2017, June 1). The Sun, Editorial. Accessed 2021 Jun 10 https://www.sunnewsonline.com/nigerias-poor-healthcare-access-ranking/[Google Scholar]

- Muanya C, Onyenucheya A (2021, Feb 4). Bridging doctor-patient ratio gap to boost access to healthcare delivery in Nigeria. The Guardian. Accessed 2021 Jun 10 https://guardian.ng/features/health/bridging-doctor-patient-ratio-gap-to-boost-access-to-healthcare-delivery-in-nigeria/ [Google Scholar]

- Adeyinka AM. Spatial distribution, pattern and accessibility of urban population to health facilities in southwestern Nigeria: the case study of ilesa. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2013;4(2):425–436. [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo O, Labiran A, Emerenini CF, et al. Health Workforce for 2016-2030: will Nigeria have enough? Int. J. Inn. Res. 2016;4(1):9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Uwala VA. Spatial distribution and analysis of public health care facilities in yewa south local government, ogun state. Int. Multi discip. Res. J. 2020;6(7):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Welcome MO. The Nigerian health care system: need for integrating adequate medical intelligence and surveillance systems. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2011;3(4):470–478. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar]

- Macrotrends.net (2021). Lagos, Nigeria Metro Area Population 1950-2021. [cited 2022 Jun]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- Ayeni A, Owolabi D. Increasing population, urbanization and climatic factors in Lagos State, Nigeria: the nexus and implications on water demand and supply. J Global Initiatives Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective. 2016;11(2):6. [Google Scholar]

- Oyediran MA. Maternal and Child Health and family planning in Nigeria. Public Health. 1981 Nov;95(6):344–346. PMID 7335846. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Vaccines Preventable Diseases.[cited 2022 Mar]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mmr/public/index.html [Google Scholar]

- National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) of the Federal Ministry of Health. National Routine Immunization Strategic Plan 2013–2015, intensify in reaching every ward through accountability. Abuja: NPHCDA; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lagos State Government. Lagos state bureau of statistics 2005. [cited 2022 Nov]. Available from: http://www.lagosstate.gov.ng/pagelinks.php?p=6[Google Scholar]

- Lagos State population. [cited 2022 Nov]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lagos_State[Google Scholar]

- Lagos state ministry of health. [cited 2022 Nov]. Available from: http://www.lsmoh.com/news/lagos-screens-women-for-rhesus-incompatibility#.VNPabizYzDc[Google Scholar]

- South West Region. My Guide Nigeria. [cited 2022 Nov]. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry of Health (2021). NIGERIA Health Facility Registry (HFR). Retrieved from https://hfr.health.gov.ng/facilities/hospitals-search?_token=(Accessed Oct 6, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Obubu M, Chukwu N, Ananaba A, et al. Lagos state health facility assessment tool. Figshare. Dataset. 2022. DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.21778871.v1 [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- City population (2021). Nigeria: administrative division; states and local government areas. Retrieved from https://www.citypopulation.de/php/nigeria-admin.php(Accessed Oct 8, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Lagos state health facility assessment (2021); HSCL and NOIPoll. [Google Scholar]

- Sani L. Distribution pattern of healthcare facilities in osun state, Nigeria. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2010;3(2):65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nullis-Kapp C. Health worker shortage could derail development goals. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(1):5–6.&nbs p;[PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Adeloye D, David RA, Olaogun AA, et al. Health workforce and governance: the crisis in Nigeria. Human Resoure Health. 2017;15(1):32. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow A, Ulloa JG, Dowling PT, et al. Predictors of primary care physician practice location in underserved urban and rural areas in the United States: a systematic literature review. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1313–1321.&nb sp;[Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- cited 2022 Jun.Availablefrom: https://radionigeriaabuja.gov.ng/maternal-mortality-fg-moves-to-reduce-512-deaths-per-100-000-births/ [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SR, Nowak RG, OrazulikeI, et al. The immediate effect of the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act on stigma, discrimination, and engagement on HIV prevention and treatment services in men who have sex with men in Nigeria: analysis of prospective data from the TRUST cohort. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(7):e299–e306.[Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Bisi Alimi Foundation (2017). Not dancing to their music [pdf] [Google Scholar]

- PEPFAR Large National Survey Shows Smaller HIV Epidemic in Nigeria Than Once Thought and Highlights Key Gaps Toward Reaching HIV Epidemic Control [Accessed Apr 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health (2010). HIV Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance Survey (IBBSS) [pdf] [Google Scholar]

- NACA (2017) ‘National Strategic Framework on HIV and AIDS: 2017 – 2021’ [pdf] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS AIDS info. [Accessed Jul 2020] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS (2017) ’Data Book’ [pdf] [Google Scholar]

- NACA (2015) ‘Nigeria GARPR 2015’[pdf] [Google Scholar]

- NACA (2015). End of Term Desk Review Report of the 2010-2015 National HIV/AIDS Strategic Plan. [pdf] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS ‘A IDS info’ [Accessed Oct 2018] [Google Scholar]

- Lekoubou A, Awah P, Fezeu L, Lekoubou, Alain, Paschal Awah, Leopold Fezeu, Eugene Sobngwi, and Andre Pascal Kengne. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus and task shifting in their management in sub-saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(2):353–363. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- “Global Health Observatory Data Repository – Health Workforce Absolute Numbers.” 2017. WHO. [cited 2022 Oct]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A1443?lang=en[Google Scholar]

- Zachariah R, Ford N, Philips M, et al. Task Shifting in HIV/AIDS: opportunities, Challenges and Proposed Actions for Sub-Saharan Africa. Trans R Soc Trop MedHyg. 2009;103(6):549–558. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A Systematic Review of Task- Shifting for HIV Treatment and Care in Africa. Human Resource Health. 2010;8(March):8. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar]